The Environmental Reality of Dissolvable Electronics

ECE Professor Ravinder Dahiya discovered that some biodegradable electronics fail to fully dissolve and instead break down into harmful microplastics that can persist in and damage the environment for years.

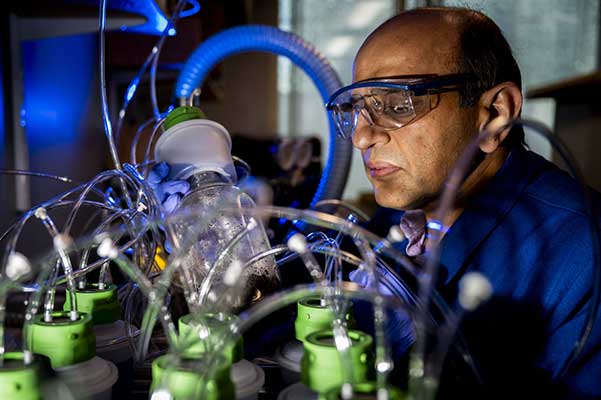

This article originally appeared on Northeastern Global News. It was published by Cesareo Contreras. Main photo: Ravinder Dahiya, professor of engineering, conducts transient electronics research in the Egan Research Center. Photo by Matthew Modoono/Northeastern University

Biodegradable technology can dissolve into harmful microplastics, Northeastern research uncovers

Ravinder Dahiya and researchers in his lab are studying electronic degradation and its damaging impact on the environment.

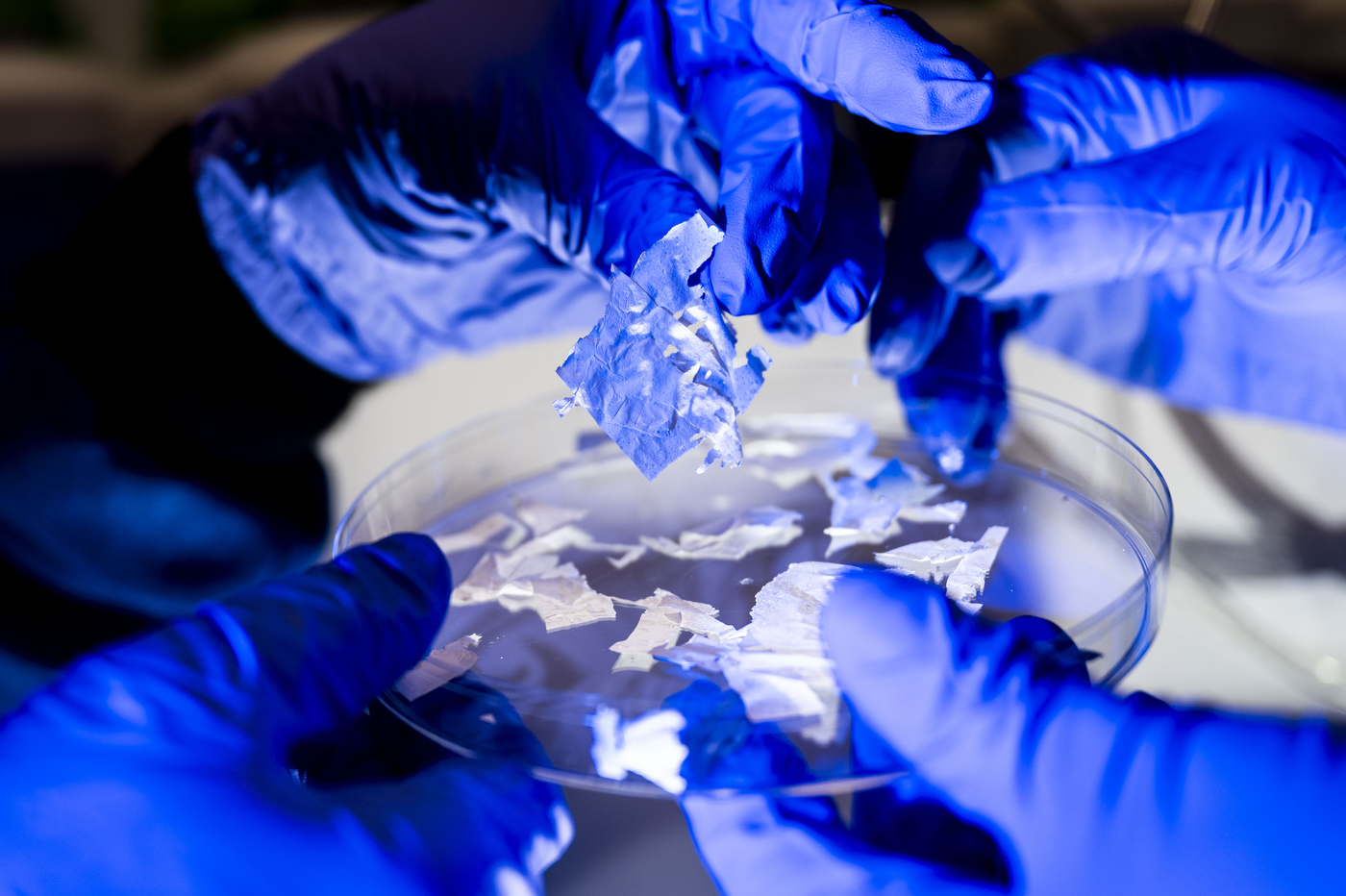

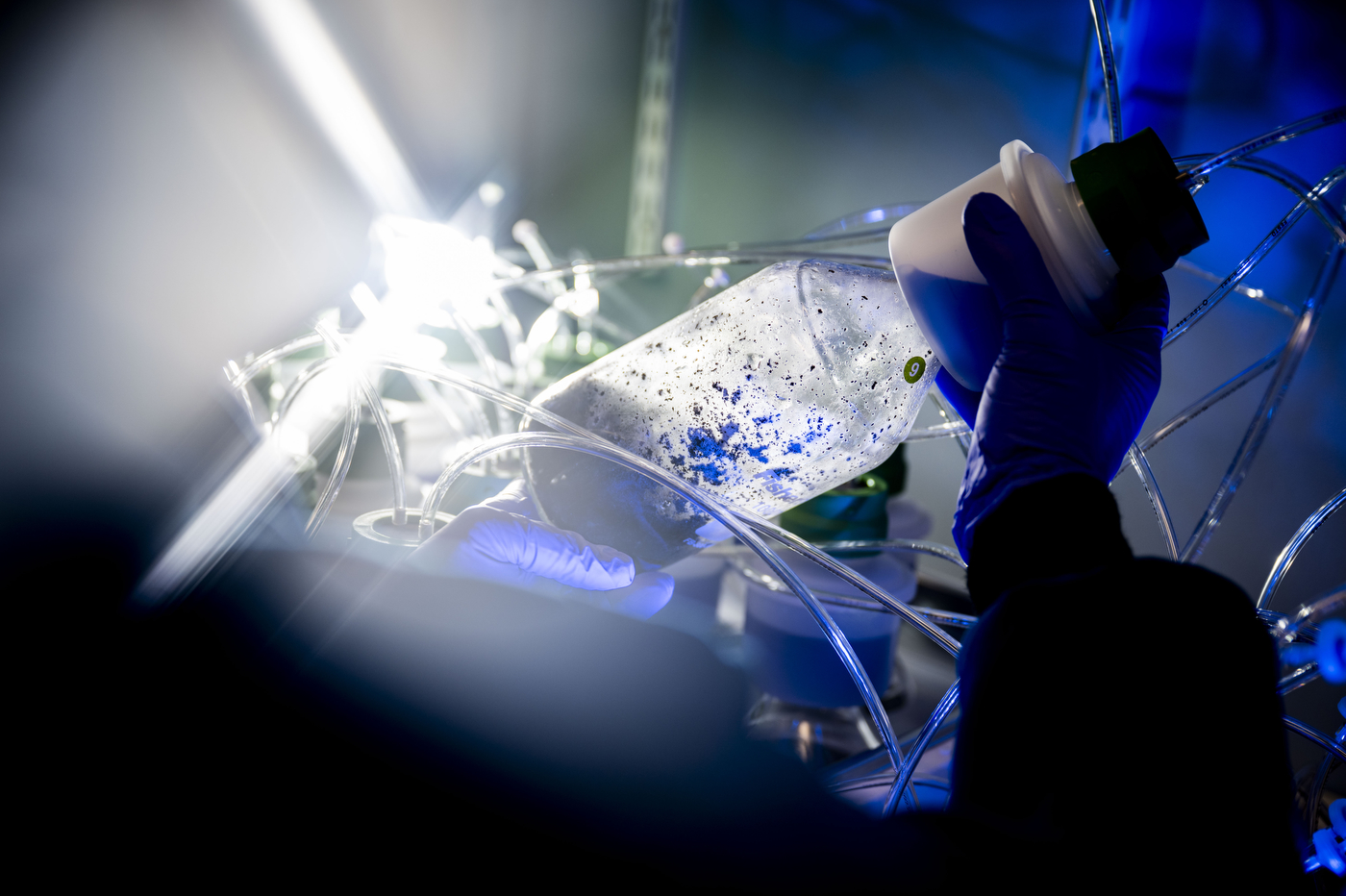

Northeastern University researchers have discovered that materials used in the development of transient electronics — devices designed to biodegrade at the end of their life — can break down into microplastics, casting doubt on the true dissolvability of these devices over time.

One particular polymer material, PEDOT:PSS, which is popularly used in medical applications, has been found to persist for more than eight years and its degradation could lead to the formation of microplastic fragments, according to Ravinder Dahiya, a professor of electrical and computer engineering at Northeastern University and one of the lead authors of the research.

Dahiya, who was recently awarded the Celebrating Editorial Impact Award by Springer Nature for his work on flexible electronics, has a keen interest in understanding how electrical systems can be prevented from turning into eventual e-waste.

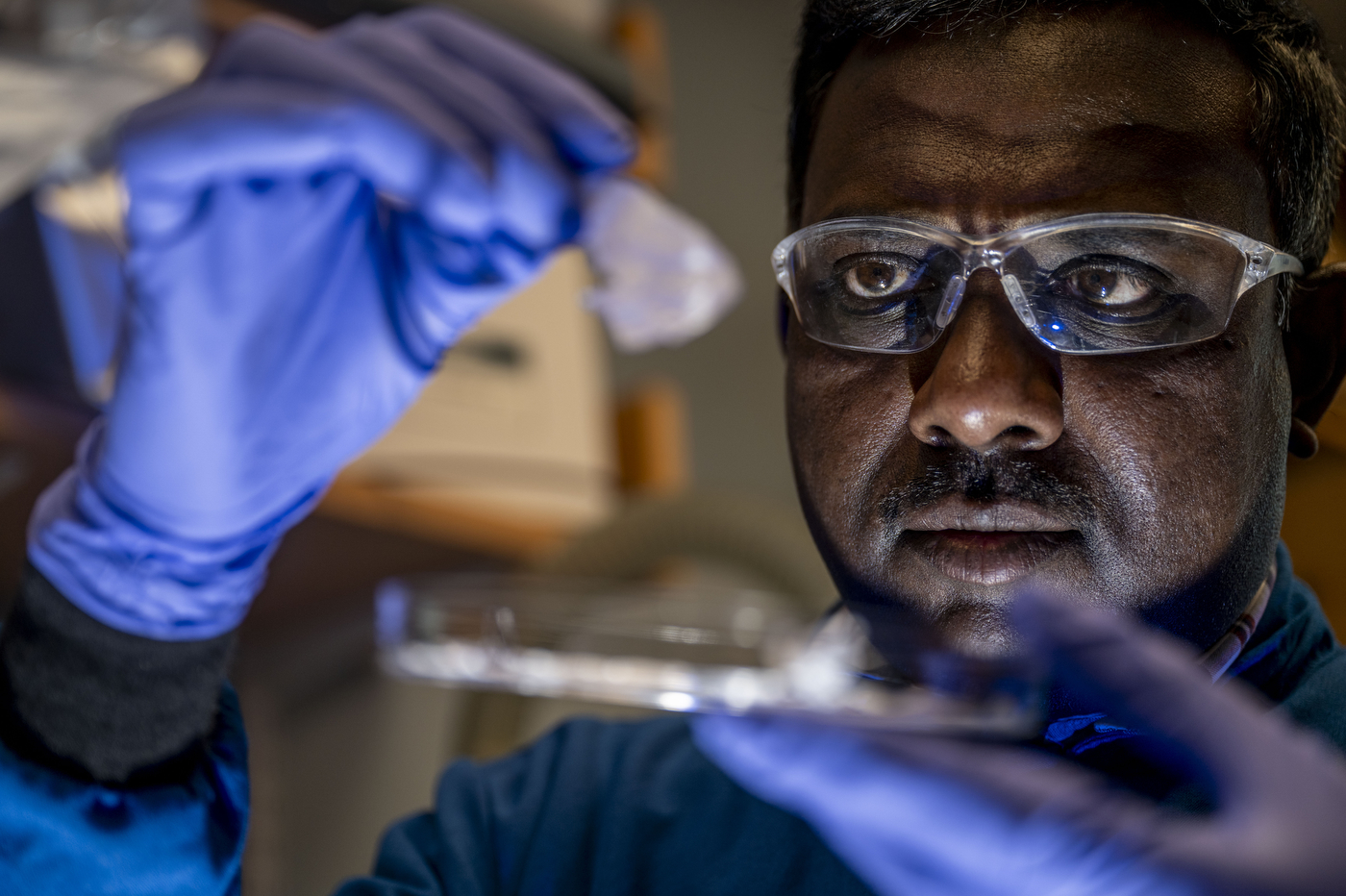

In the research, which was published this year, Dahiya and Sofia Sandhu, a former post doctoral researcher in his lab, investigated the biodegradability of two transient electronic devices — a partly degradable pressure sensor and a fully degradable photo detector.

|

|

|

|

Ravinder Dahiya, professor of engineering, and Dhayalan Shakthivel, a postdoctoral researcher, conduct transient electronics research in the Egan Research Center. Photo by Matthew Modoono/Northeastern University

In their observations, they highlighted the importance of proper material selection in the development of these technologies. Whereas polymer materials such as cellulose and silk fibroin have high rates of degradation and release byproducts that are not harmful to the environment, others can be quite dangerous, such as the previously mentioned PEDOT:PSS.

“You have to look at these materials carefully,” Dahiya said. “Normally at the end of their life, electronics are dumped into the soil. When you put an electronic board in soil, we need to understand if the electronic board, during the degradation process, is enriching the soil or if the soil is unaffected. In some cases, degradation might damage the soil permanently, and that is a big environmental and health issue.”

Read full story at Northeastern Global News