Creating Low-Cost, Low-Power Sensors to Protect Crops

Matteo Rinaldi, ECE Associate Professor and Director of Northeastern SMART, is developing low-cost, low-power sensors that can monitor the health of a farmer’s crop and alert them when there is trouble.

Crops communicate with one another. These researchers want to listen in.

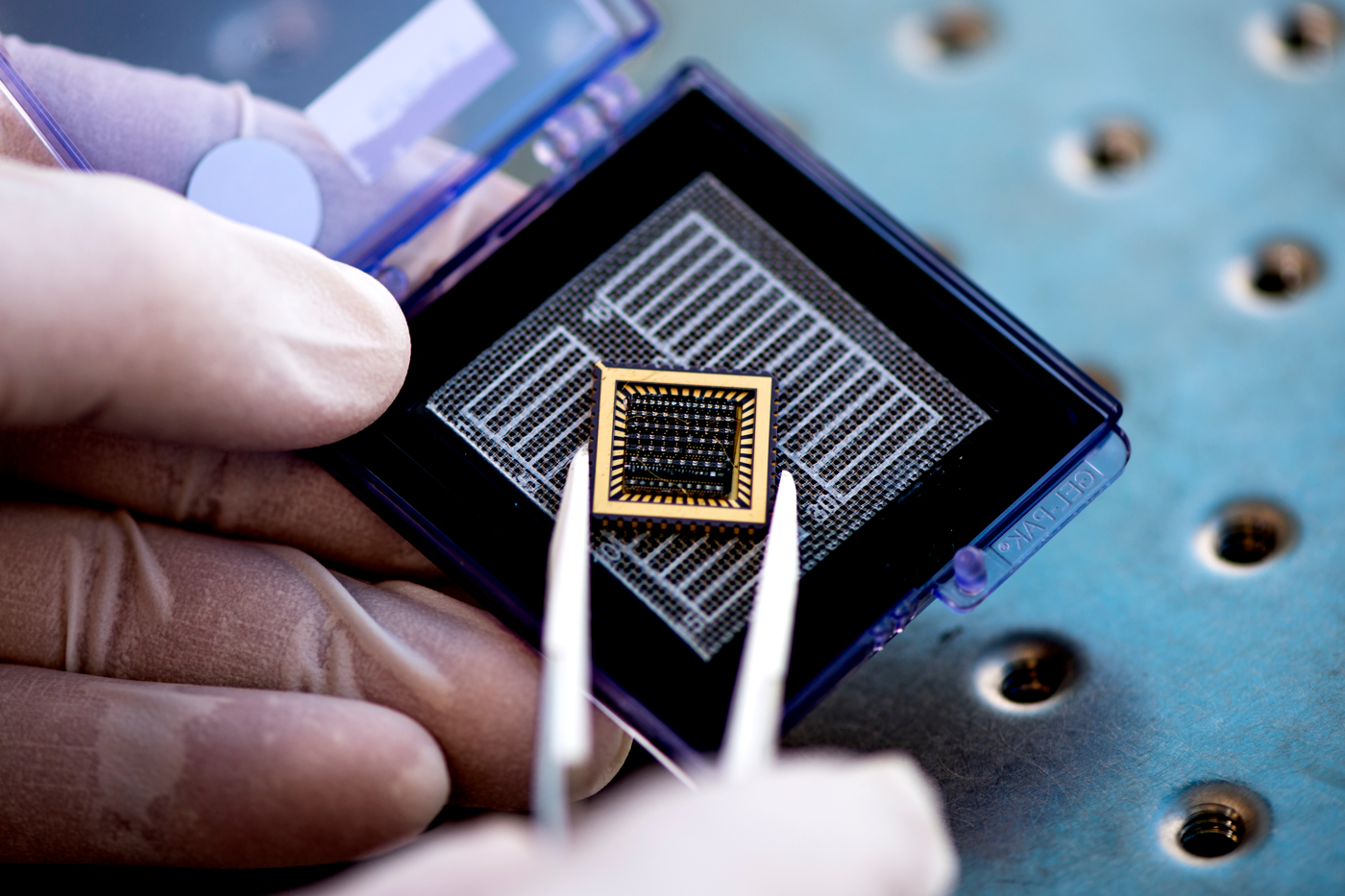

Photo: Researchers at Northeastern are designing a low-cost, low-power sensor that will detect the volatile organic chemicals given off by damaged plants. Matthew Modoono/Northeastern University

Pests and disease are a farmer’s worst enemies. If they’re not caught early enough, they can decimate a crop. But most new technologies that monitor crop health aren’t feasible for farmers in low-income countries to use: They’re too expensive, and they require a constant source of power.

A group at Northeastern University, funded by a grant from the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, is designing low-cost, low-power sensors to help farmers detect problems before they can spread.

“State-of-the-art sensors use batteries or electrical power to keep them awake and sensitive to environmental change,” said Matteo Rinaldi, the director of Northeastern SMART, a new center focused on developing technologies to make everyday life safer, easier, and more efficient. “Instead, our sensor harvests power from the signal we want to detect.”

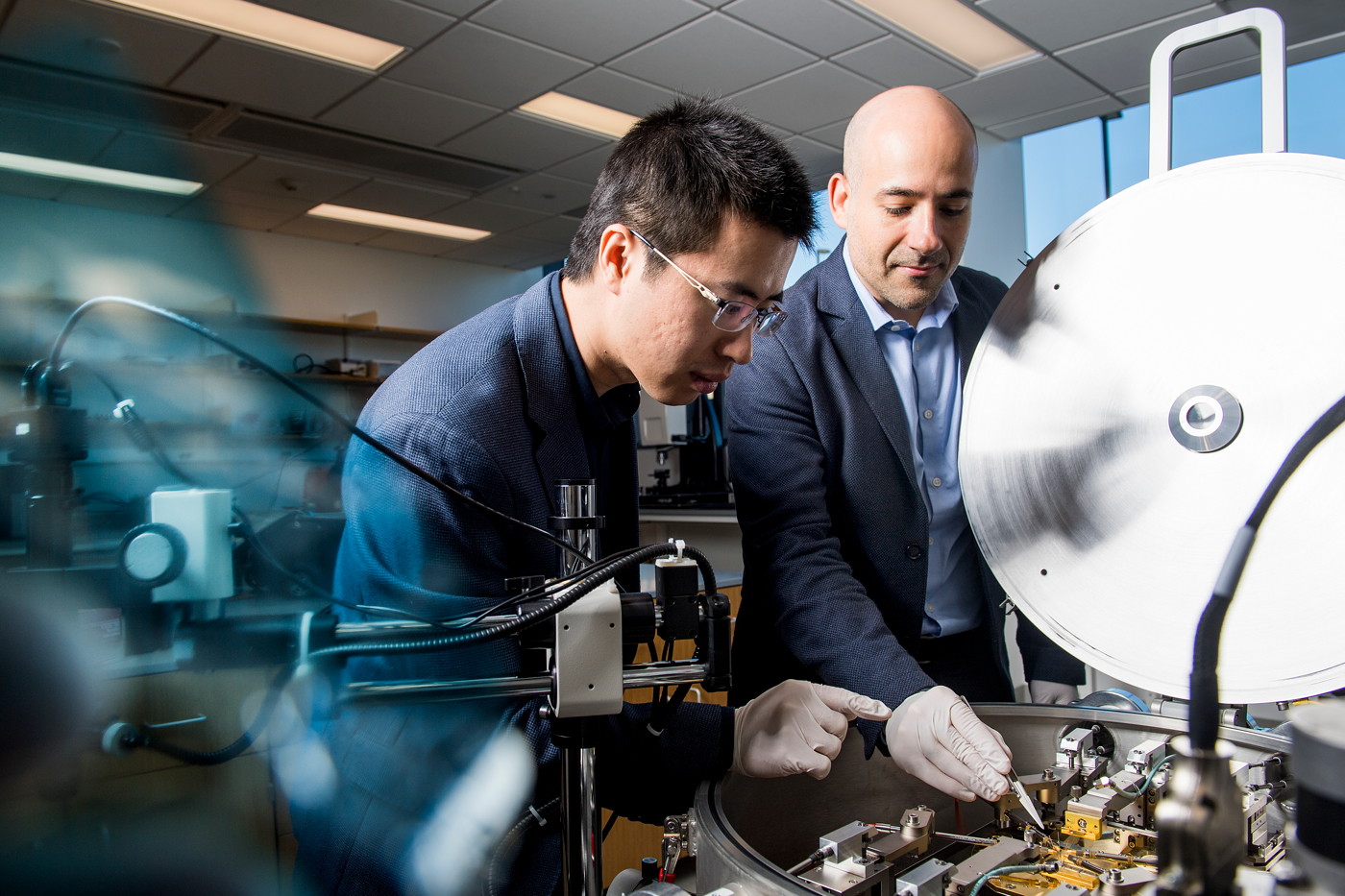

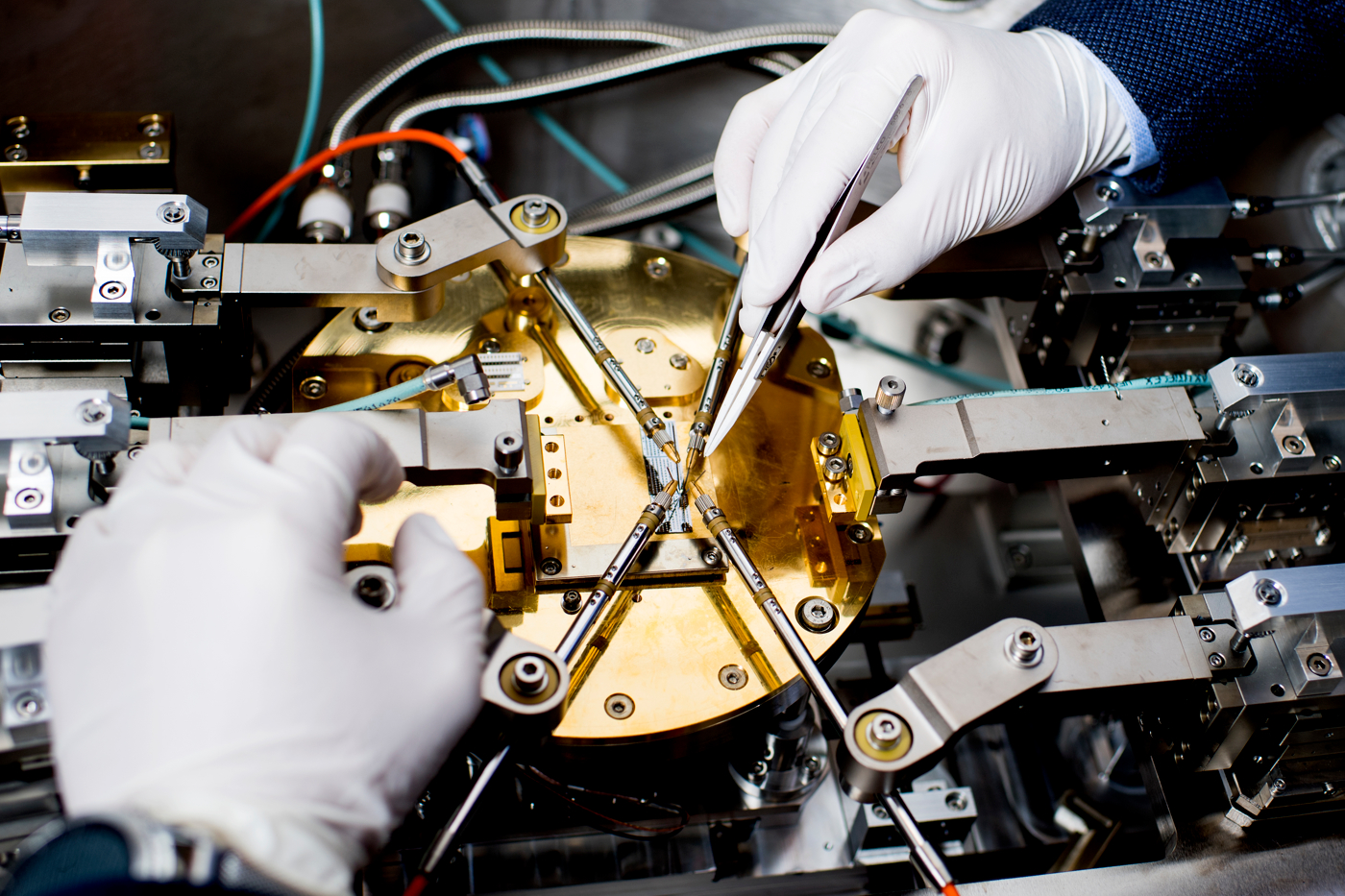

Matteo Rinaldi and Zhenyun Qian conduct research in the Interdisciplinary Science and Engineering Complex. They have received a grant from the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation to design low-cost, low-power sensors that will help farmers detect pests and disease before they can spread. Photos by Matthew Modoono/Northeastern University

That signal is a group of chemicals that plants give off when they have been damaged. When plants are infected by a disease, struggling to find water, or colonized by hungry insects, they produce volatile organic chemicals to communicate with each other and other species. These chemicals can warn other plants of the danger, or summon predatory insects to eat the pests gnawing on their leaves.

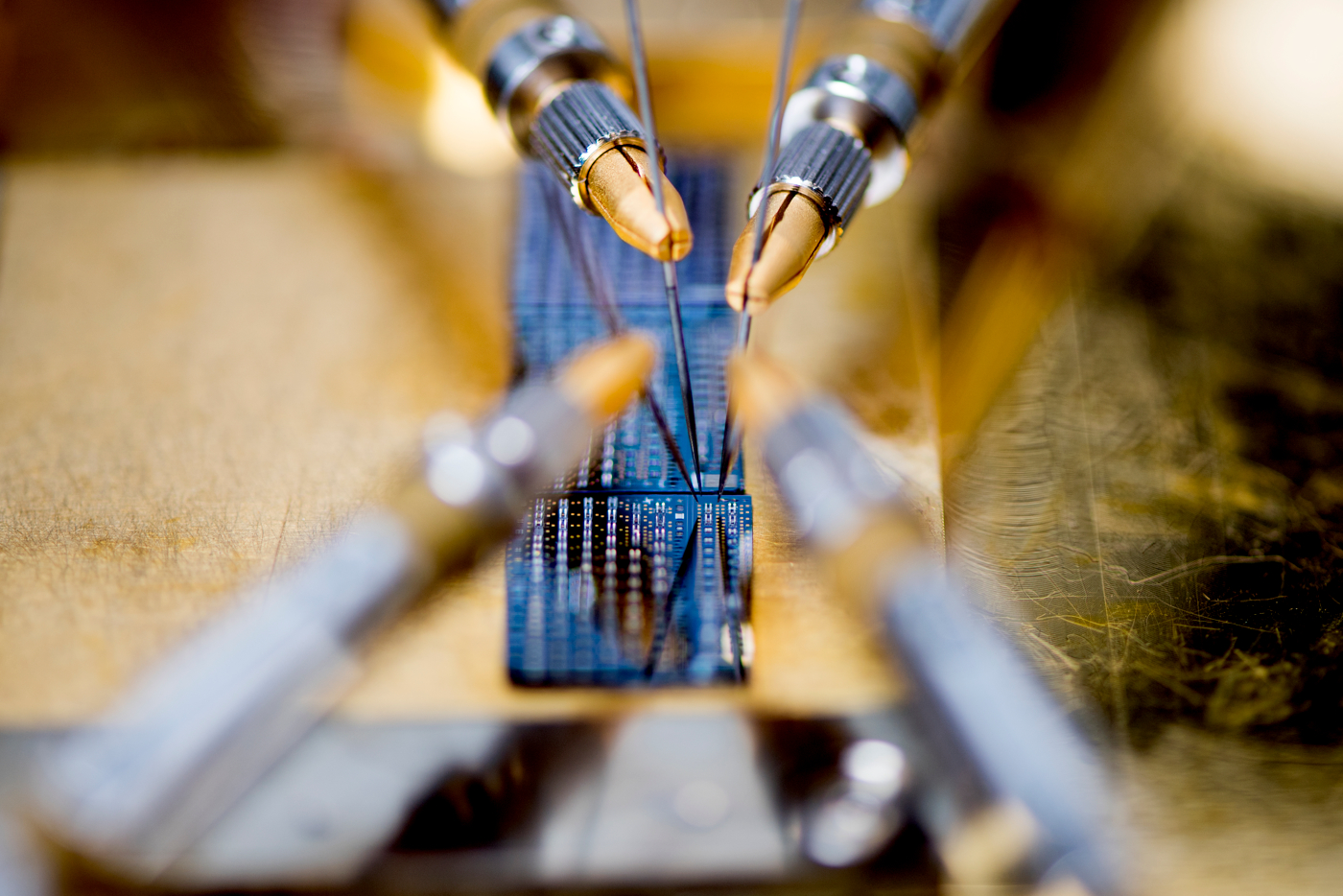

Rinaldi, who is an associate professor in the Department of Electrical and Computer Engineering and the principal investigator on the project, intends to use these volatile organic chemicals to trigger a chemical reaction in a sensor. The reaction will act like a switch, turning on a circuit to connect the system to an otherwise unused battery. Then the device can use the battery power to wirelessly broadcast a signal to alert the farmer that there is a problem.

“When the chemical is not present, then the sensor will consume absolutely zero power,” said Zhenyun Qian, a research assistant professor in the department who will be working on the project. “Only when the chemical released by the plant is actually near will the device be activated.”

Since the device doesn’t require power until it is activated, it can remain on standby until the end of the battery’s natural lifetime, which could be as long as a decade, Qian said.

While earning his doctorate at Northeastern, Qian worked on a similar sensor to detect infrared light. These sensors could be mass-produced for about five cents each and were roughly the size of a quarter.

“By the end of that project, we were thinking generally about this concept of zero-power sensors,” Qian said. “Where is the most-needed application for this technology?”

The researchers sent a proposal to Grand Challenges Explorations, an initiative of the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation that supports research to solve global health and development problems. One of the 2018 challenges focused on developing tools for pest and disease surveillance of crops in low-income countries.

|  |  |  |

Photos by Matthew Modoono/Northeastern University

In November, the foundation announced that the researchers from Northeastern were among the 10 groups to receive initial funding for that challenge. Small, inexpensive sensors distributed across large fields could help farmers keep an eye on their crops and provide data about larger trends in the area.

Now, the group needs to prove they can build one.

“As populations continue to grow worldwide, we need to increase our food production,” Rinaldi said. “Being able to monitor very large crop fields in real-time will help farmers make the best decisions to maximize their yields and has the potential to make a huge impact on society.”

by Laura Castañón, News @ Northeastern