Improving the Safety and Efficiency of Airports

ECE Professor Michael Silevitch and Carey Rappaport have been working with the Department of Homeland Security for the last fifteen years to improve safety and efficiency at airports and other public settings.

This article originally appeared on Northeastern Global News. It was published by Ian Thomsen. Main photo: Travelers make their way through a TSA screening line at Orlando International Airport ahead of the July 4 holiday. Hundreds of flights across the county have been delayed or canceled and airlines are warning passengers to prepare for issues. (Photo by Paul Hennessy / SOPA Images/Sipa USA)(Sipa via AP Images)

Will airport security checkpoints become more efficient?

Northeastern researchers have been partnering with the Department of Homeland Security on projects to improve safety and efficiency at airports and other public settings.

The Sunday after Thanksgiving threatens to be the busiest travel day of the year — featuring long passenger lines at airport security checkpoints that yield anxiety and frustration.

Researchers at Northeastern are working on that.

Since 2008 they’ve been partnering with the Department of Homeland Security to pursue safety and efficiency in a variety of public settings. Recent work has included improvements to full-body scanners at airports as well as a complex system that connects passengers with their luggage at checkpoints.

Carey Rappaport, Northeastern distinguished professor of electrical and computer engineering. Photo by Alyssa Stone/Northeastern University

Additional research is being done on behalf of so-called “soft targets” — stadiums and arenas, schools and houses of worship, even public sidewalks — where, eventually, a medley of sensors will be deployed to fend off weapons of mass destruction.

Northeastern’s role in finding and mitigating terrorist threats developed from an unlikely source. The alliance with Homeland Security can be traced back more than two decades to work undertaken by Michael Silevitch, a professor who was directing multiple research tracks that appeared to have little in common — including one to detect breast cancer tumors.

“If you think about how you diagnose a tumor, the simple way is with mammogram X-ray scans,” says Silevitch, the Robert D. Black Professor of Electrical and Computer Engineering at Northeastern who serves as director of SENTRY, a Homeland Security Center of Excellence comprising more than 20 universities headed by Northeastern. “You take a set of 2D images using a CAT scan technique called tomosynthesis, which we helped develop, and you fuse that with other kinds of sensors to get a very accurate 3D representation of the structure in the breast.”

Similar methods were applied to discover smuggling tunnels as well as buried landmines and deposits of nuclear waste. That work was overseen by Northeastern’s Engineering Research Center based on a 10-year grant from the National Science Foundation — a breakthrough award (2000-2010) that “showed that Northeastern could compete with any research university in the country,” says Silevitch.

Northeastern was initially tasked by Homeland Security to focus on detecting explosives at airports 15 years ago. “People would ask me about the Engineering Research Center — ‘What does it do?’ — and I would say, ‘We find hidden things,’” says Silevitch, its director. “When Homeland Security put out a request for proposals for detecting threats in luggage — well, there’s no difference in terms of the strategies that you use to find a hidden tumor in the body or a hidden bomb in a suitcase. So that allowed us to win a very competitive 10-year Center of Excellence award called ALERT in an area where we had no prior experience.”

|  |

| |

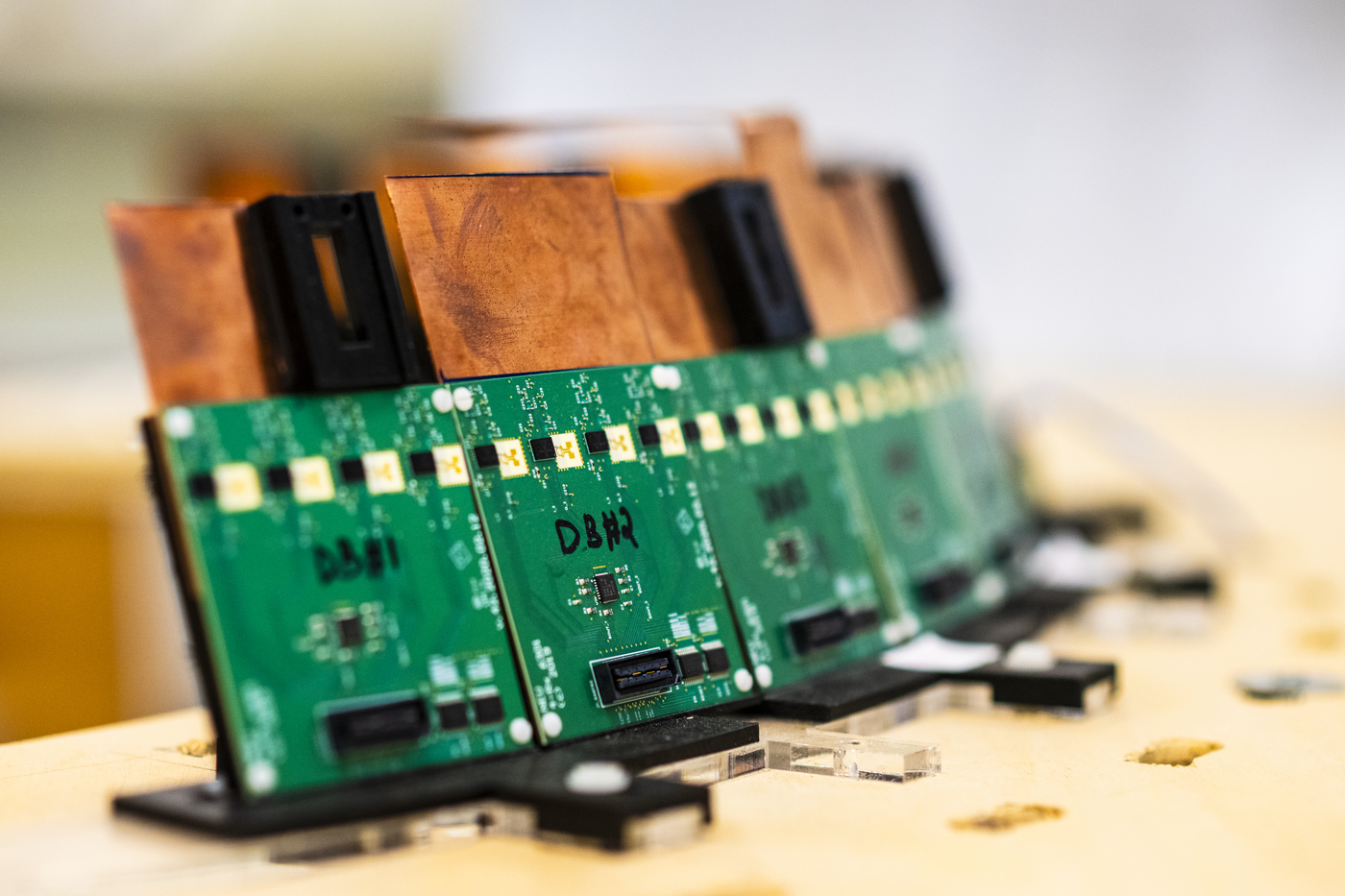

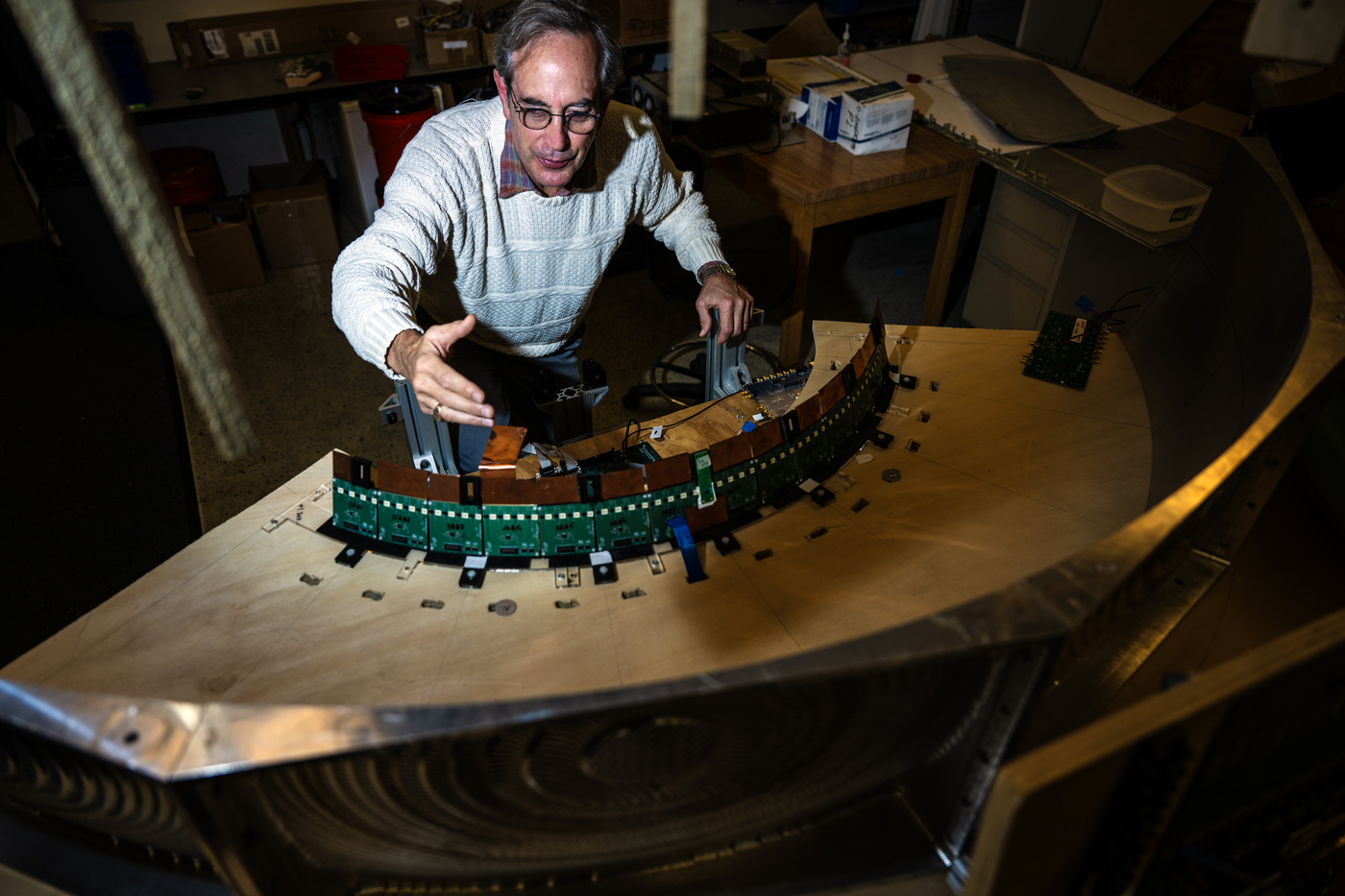

Rappaport built a prototype of an improved full-body scanner that could reduce errors. Photos by Alyssa Stone/Northeastern University

Solving the ‘left-behind’ problem

The advent of full-body scanners has made a positive impact on U.S. airport security since 2010, says Carey Rappaport, a College of Engineering Distinguished Professor.

“It’s night and day,” says Rappaport, who helps direct three government-funded security centers at Northeastern.

The vulnerability of traditional metal detectors is obvious: They’re unable to detect weapons made of plastic and other non-metals. The new scanners emit radiofrequency waves to locate suspicious objects of all kinds hidden within a passenger’s clothes.

Early versions of the machines infamously captured naked images of the body. That invasive technology has been replaced by machines that reveal no personal features. Instead, Transportation Security Administration (TSA) agents are provided access to generic body images featuring one or more small yellow boxes that mark the location of objects that require additional scrutiny.

An issue with the machines has been a large number of false positives triggered by slight movement, Rappaport says.

“It’s like kids moving around when you’re trying to take pictures,” Rappaport says. “All it takes is just a little hiccup. My own record going through an airport scanner is 17 yellow boxes, even though I didn’t have any anomalous objects with me.”

Read full story at Northeastern Global News