Using Recycled Paper to Cool the Air

MIE Associate Professor Yi Zheng developed a “cooling paper” that could help cool the air in homes and businesses without the use of electricity.

How to keep cool without turning on the A/C

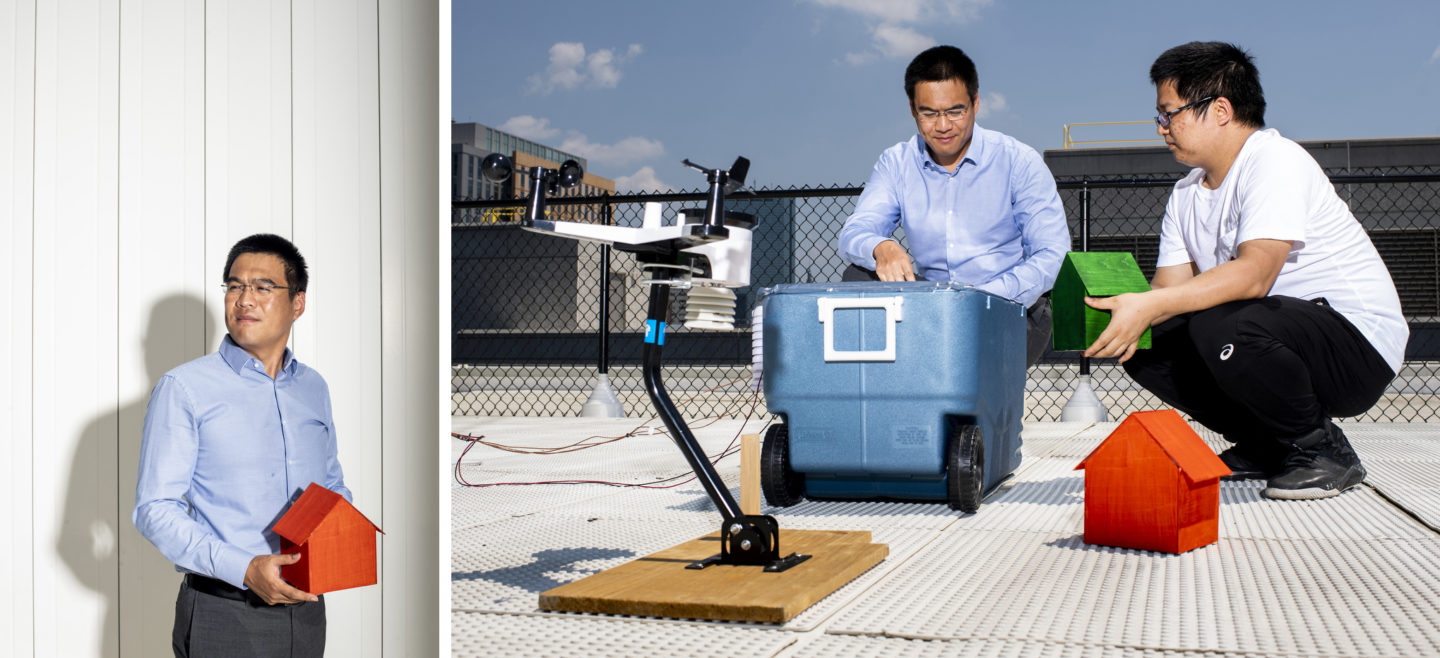

Main photo: What if buildings could stay cool all on their own—no electricity required? That’s the premise of a new invention by Yi Zheng, associate professor of mechanical and industrial engineering at Northeastern. Photo by Ruby Wallau/Northeastern University

The sun beats down, making everything you touch radiate burning heat. Beads of sweat form all over your body, even when you sit still. It’s one of those beastly hot summer (or spring) days.

Then, you go inside your house and turn on the air conditioning to its highest setting. Ah! Sweet relief!

But your energy bill also feels the effects of the heat. So what if the building could keep cool all on its own—no electricity required?

That’s the premise of Yi Zheng’s new invention. The associate professor of mechanical and industrial engineering at Northeastern has created a sustainable material that can be used to make buildings or other objects able to keep cool without relying on conventional cooling systems.

|  |

|

Yi Zheng, associate professor in the College of Engineering, and graduate student Yanpei Tian study the capacity of their “cooling paper” to reduce the temperature inside a structure on the rooftop of Snell Engineering. Photos by Ruby Wallau/Northeastern University

Zheng envisions this material covering the roofs of houses, warehouses, office buildings, or other edifices. It also could be incorporated into the materials used to construct the buildings, too, he says.

The material, which Zheng has dubbed “cooling paper,” works in two ways. Its light color reflects those warm solar rays away from the building, and it also sucks heat out of the interior, too. Wait, you may be saying, shouldn’t reflecting the heat away be enough? No, actually, because the sun isn’t the only thing warming up our homes. Electronics, cooking, and human bodies generate warmth, too. The porous microstructure of the natural fibers in the cooling paper absorbs that warmth and re-emits it away from the building.

Cooling paper is, in fact, made of paper. One day, Zheng, who studies nanomaterials, saw a bucket full of used printing paper. He recalls thinking to himself, ‘How could we simply transform that waste material into some functional energy material, composite materials?’

So, with the help of a high-speed blender from his home kitchen, Zheng made a pulp out of paper waste and the material that makes up Teflon. Then he formed it into water-repelling “cooling paper” that could coat homes. Then, he and his team tested its capacity to keep cool under various temperature and humidity conditions.

Zheng and his colleagues found that the cooling paper can reduce a room’s temperature by as much as 10 degrees Fahrenheit. He selected materials that would reduce the cost of deploying this new technology to cool homes. The process for creating and testing the new material was described in a paper published last month in the American Chemical Society journal Applied Materials & Interfaces. Zheng was awarded a National Science Foundation CAREER Award grant in 2019 for his research.

Yi Zheng, associate professor of mechanical and industrial engineering, created a new recyclable material that can be used to cool down buildings without relying on conventional cooling systems. Photo by Ruby Wallau/Northeastern University

The cooling paper isn’t just eco-friendly in its ability to reduce your energy footprint. It’s also recyclable. The material can be used, exposed to solar radiation, weather, and varying temperatures, then reduced to a pulp (again) and reformed without losing one iota of its cooling properties. Zheng has tried it. And the recycled cooling paper performed just as well as the original.

“I was surprised when I obtained the same result,” Zheng says. “We thought there would be maybe 10 percent, 20 percent of loss, but no.”

Zheng doesn’t just aim to reduce your utility bills through his research. He also hopes that his work will help combat climate change.

“The ultimate goal is to reduce global warming,” Zheng says. “The starting point is to reduce the use of carbon-based materials and also to reduce global warming.”

by Eva Botkin-Kowacki, News @ Northeastern

This research was also featured in The Hill.